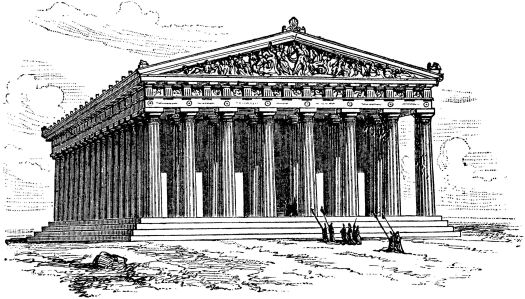

Architectural styles, often based on classical Greek & Roman precedents and/or medieval precedents, cycled in and out of fashion for centuries. Each revival introduced new variations in forms, materials, and ornamentation. Throughout this time period, however, the overall compositions remained remarkably similar to the works which were the original sources of inspiration. This continued into the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when, for some progressive architects, the connection to the forms of the past was combined with the connection to the technology of the present.

The industrial revolution in the West resulted in a proliferation of factories which became the inspiration for a new style of architecture: early modernism. Factories and industrial buildings contained a rational structural grid allowing for long spans and flexible/open floor space. Generally speaking, the facades were simple and sported little or no ornamentation. And of course the factories also contained machines, which provided further inspiration for some, as we will see.

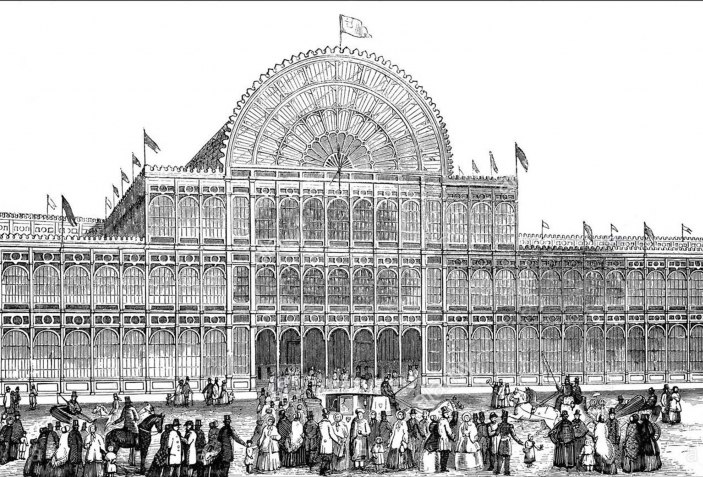

New materials were introduced which allowed the willing architect an unprecedented level of design freedom. Such materials included iron (and later steel), plate glass, stucco, and glass block. Greenhouses and buildings such as Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, used large expanses of plate glass and thin iron fabrications. These inovations allowed unprecedented quantities of light to flood the buildings. These buildings also used standardized and mass produced components, allowing for faster building erection and deconstruction and resulting in lower costs for both labor and materials.

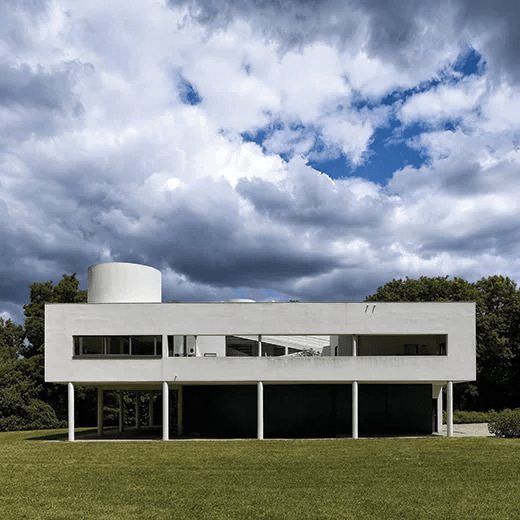

Architects such as Alfred Loos, Peter Behrens and Otto Wagner pioneered this new style. But it was the Swiss born architect LeCorbusier, who refined and codified it. He refined it through the design and construction of a series of villas in the 1920s. These villas demonstrated machine-like precision. He codified it through the publication of his Five Points of Architecture. These five points are well illustrated in the Villa Sayoye, which was completed in 1931 in Poissy France. They are: columns which raise the building above the ground, a flexible and open plan, a functional roof garden, ribbon windows, and curtain walls.

The roof garden is separated from the interior by a large expanse of plate glass. The columns support the floor, meaning that the exterior walls are not load bearing and may act simply as “curtains”. Curved forms and ramps reflect movement and contrast with the orthogonal rigor of the structural grid.

Our first impression is that the building is not only devoid of ornamentation but also devoid of historical precedence. Such is not the case. In 1911 LeCorbusier traveled throughout central Europe and spent three weeks studying and sketching the Acropolis. He subsequently wrote: “The Greeks built temples on the Acropolis which answer to a single conception, and which have gathered up around them the desolate landscape and subjected it to the composition. So from all sides of the horizon the conception is unique. That is why no other works of architecture exist which have this grandeur.” In the Villa Savoye we can see LeCorbusier working with a simple geometric form which dominates the landscape, and which is unique from every vantage point. Finally, he is seeking grandeur in the form of what he called a “machine a habiter,” a machine for living in.

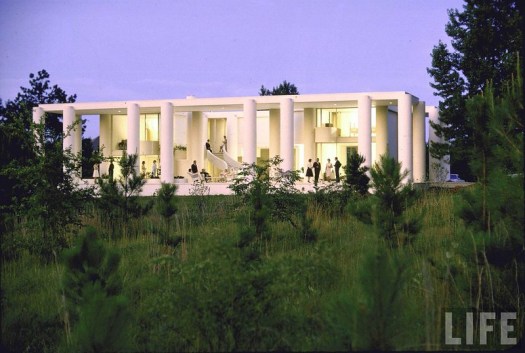

This new “looser” way of connecting to the architecture of the past conditioned throughout the 20th century, including an Athens Greece to Athens Alabama connection! You can find out about that in My Big Fat Greek Architecture. Thanks for checking out this blog post and stay tuned for another ArchitectureConnection soon!