The earliest structures built by mankind were simple shelters designed primarily to keep the elements out. The builders were hunter-gatherers and their structures were temporary and transient. They were not what we would consider “Architecture” (with a capital A). As mankind progressed to higher degrees of civilization, and as the division of labor came about, he began to think of built structures as more than simple shelters. These structures began to reflect elements of art – a required component in “Architecture”. But when exactly did this transformation take place? I’m not sure we can tie it to a precise time, although I think we can identify a time period. I am reminded of a scene in the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding in which the father of the bride is able to trace any word back to the Greek root. In much the same way, I contend that all “Architecture” (at least in the West) can connect back to Greek roots.

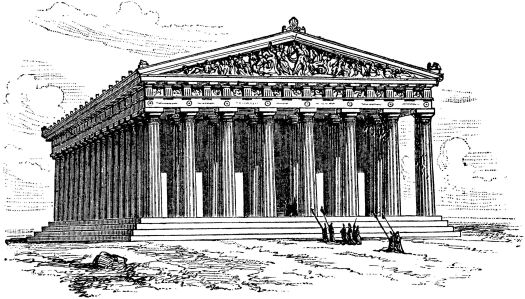

The Classical Greek period lasted from the 5th to the 4th centuries BCE. Classical Greek buildings such as the Parthenon in Athens, completed in 438 BCE, later inspired the architect-builders of the Roman Empire. The Romans adopted and adapted the architecture of the Greeks. Over the centuries, the style periodically fell out of favor, but it has been consistently resurrected in a slightly modified forms, in revival styles.

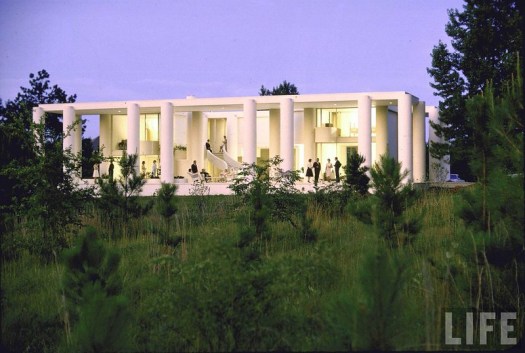

Architecture can be connected to these Greek buildings without being stylistically similar. The forms, massing, scale, and rhythm derived from these works can be devices used by the creative architect, whether or not the architect is practicing in the “classical style”. A fine example of this may be found in another Athens – Athens, Alabama. Paul Rudolph, perhaps the most prominent architect of his day, designed a home for Mr. and Mrs. John W. Wallace. The house was featured in many journals, including a 1964 Life magazine article. Following are Rudolph’s own remarks regarding the house:

“Years ago I designed a house in Alabama based on Greek revival architecture of the South. I was brought up in that area, I knew it well, and my first memories of architecture were the Greek Revival buildings of the area and the sharecroppers’ cottages, both of which intrigued me no end. Both seemed to have a complete validity – in other words, vernacular and so-called high architecture. This house in Alabama has double-story-high porches on four sides, over-scaled columns not based on structural need but on character – yet it’s a modern house. It doesn’t ever deal with Greek columns, capitals and bases, cornices, nor the use of symbols, but the image of the south is very clear. The design comes from the climate, the environment, how people live, what was suitable. It gets very hot in summer; therefore, the enclosure is put in man-made shade, which lowers the energy consumption of the air-conditioning system. It has many symmetrical parts, but the circulation and spatial organization is asymmetrical. If you know the location of this house it is clear that it really comes from the Greek Revival architecture of the South, but it certainly doesn’t have any Greek Revival symbols, although its image is similar because it tries to solve some of the same problems.”

Davern, Jeanne M. “A Conversation with Paul Rudolph.” Architectural Record 170 (March 1982): 90-97.

I contend that much can be learned from the architecture of the past. It can inspire and inform, as classical architecture inspired and informed Paul Rudolph in his design of the Wallace Residence. I do, however, question the practice of some to literally duplicate large portions of prior works. In my view, neither the copied work nor the derived work benefit. If architecture (or any other form of art) is not of its time, it becomes overused and stagnant.

Next time we’ll explore the roots of modernism and see how architecture connects to technology in ….. A Machine for Living In. Spoiler alert: Remember that all “Architecture” (at least in the West) can connect back to Greek roots.